What is the Notwithstanding Clause?

Allow me to wade into a bit of a controversy of constitutional interpretation around section 33 - the notwithstanding clause.

I've written about it before, but I want to discuss a bit more about what it does.

Lately we've been hearing more and more about it being a mechanism by which legislators can impose their own interpretation of the Charter: The court finds that a right includes x, or that y isn't a reasonable infringement, and the legislature disagrees with the court, so has a right to legislate based on its own interpretation.

In the recent Toronto v. Ontario decision from the SCC, the majority seemed to endorse that approach:

Where, therefore, a court invalidates legislation using s. 2(b) of the Charter, the legislature may give continued effect to its understanding of what the Constitution requires by invoking s. 33 and by meeting its stated conditions

There are several problems with that theory, however.

The alternative approach, which I prefer, is that s.33 creates a mechanism by which legislatures can and do simply ignore the specified Charter rights - prioritizing their own policy objectives over specified Charter rights. It's truer to the language of s.33, truer to what legislatures actually do, and truer to the democratic conversation we need to have around invocations of s.33.

The Legislature is not a Constitutional Interpreter

One of the most fundamental characteristics of Canadian civics is the separation of powers between legislative, executive, and judicial functions. Legal interpretation, up to and including constitutional interpretation, has always fallen squarely into the purview of the courts. Legislators pass laws; the executive proclaims them; the courts interpret them.

The Supreme Court of Canada is an apex court, sitting at the top of our judiciary, interpreting laws and constitutional language in a way that binds everyone else. And, within our legal milieu, the apex court is, by definition, always right.

Don't get me wrong: I can and often do disagree with the courts, including the Supreme Court, but because they're the final word on interpretive matters, even if it's an unreasonable and deeply problematic decision, that becomes the law. You can call it "bad law"; you can call it "inconsistent with first principles"; etc.; but it's not really correct to call it "wrong".

(I joke that, because they got my middle initial wrong when citing my paper in Matthews, there's no appeal from that and my legal middle name is now "Bouglas". Taking their infallibility a bit too far...but just a bit.)

If the legislature has its own constitutional interpretive function (if weirdly limited to only certain constitutional provisions), which supersedes that of the courts, then that removes from the SCC the mantle of the apex court, and puts it on the legislature - but without any of traditional expectations of a court, like impartiality or a duty of fairness.

There are several problems here, not the least of which is that it's not a role we expect or should expect the legislature to play.

A Fair and Impartial Tribunal

A judicial function like legal interpretation, as a matter of procedural fairness and Rule of Law, ought to be performed by an impartial and qualified decision-maker, in a process that gives stakeholders a meaningful opportunity to be heard and to have their submissions taken into consideration.

The legislature is many things, but not that. Legislators are not elected for their legal interpretive acumen; they do not generally owe procedural fairness obligations when crafting policy; and they are not at all impartial. To give the Legislature an effective right to sit in appeal of a Supreme Court decision undermines Rule of Law, by putting an inherently judicial function outside the scope of an independent judiciary.

By contrast, it's perfectly coherent to see the legislative override as simply being one that leaves the interpretive function solely within the purview of the courts, while allowing the legislature to prioritize its own policy objectives over the rights enumerated in sections 2 and 7-15. (We can disagree on the virtues of that constitutional approach, but it's a framework that's easy to make sense of without rewriting our entire sense of the separation of powers.)

An Unclear Role for the Public

The appeal of letting elected officials have the final word is that it goes to democratic principles: If we don't like what they're doing, in theory, we have our recourse at the polls.

So, by extension, if we don't agree with their invocation of section 33, we can vote on that, right? Sure...but on what basis are we disagreeing with it?

If the legislature is exercising an interpretive prerogative, then the electoral question becomes not just one of public policy (i.e. whether the policy objectives are worth any particular consequences), but it's also an invitation to the public to engage in the merits of the legal interpretive exercise.

Legal interpretation is perhaps one of the most arcane and inaccessible disciplines of any governmental function. If there's no impartial authority for legal interpretation, then this leads to the 'populization' of legal discourse, where voters are inclined to interpret the law in whatever way best suits their ideology, without regard to the various interpretive principles and priorities that typically guide courts.

To put this into a real-life scenario, Doug Ford invoked the notwithstanding clause to enact a law that limited speech during an election period, to replace a statute that was struck down because it wasn't minimally impairing.

The finding that the law wasn't minimally impairing was made by a well-qualified judge, following a robust hearing where the Province led evidence and made sophisticated legal submissions. The evidence and submissions leading to this finding are not particularly accessible to the public.

So if we're talking about an interpretive disagreement - the judiciary found it's a breach of s.2, which isn't minimally impairing, but Doug Ford disagrees and thinks it's either not a breach of s.2 or that it is minimally impairing - how able is the public to evaluate for itself the quality of Doug Ford's position, without the benefit of the evidentiary record underlying it, the legal submissions justifying it, or the legal training necessary to make sense of those submissions? (Furthermore, how can we even have an intelligent conversation about the government's 'interpretation' when we don't even know whether their conclusion is that it's not a breach of s.2 in the first place, or simply that they think it is minimally impairing?)

Put simply, if the legislature is exercising an interpretive function, that means we're litigating constitutional interpretation issues in the court of public opinion, and that's exactly the wrong place to litigate those.

On the other hand, if we leave the interpretive function within the exclusive purview of the judiciary, and say we're allowing the legislature to prioritize policy over s.2 rights, that's an easier discussion to have: We assume that the court was 'right' that this law breaches s.2 and isn't demonstrably justifiable in a free and democratic society, BUT as voters we get to have a conversation about whether or not the underlying policy objectives are worth it to us anyways.

An Unrealistic Picture of What's Actually Happening

Where the legislature invokes s.33, that's not usually the culmination of a careful constitutional interpretive process that concludes the judiciary got it wrong.

Quite the contrary, really.

One of two things is going to be the case when s.33 is invoked. Either the courts have struck down the same law already, or they're being proactive because they expect that the courts will find it to violate Charter rights. In other words, it's the doubtful constitutionality (based on applicable legal tests) that drives the invocation of s.33.

They try to justify it to the public on the basis of their majoritarian (pluralitarian?) democratic mandate giving them a right to make these policy decisions, and that judicial review of laws - despite being literally a centuries-old tradition - is an undemocratic exercise of political power by activist judges. The party leadership often then speeds the bill through, without meaningful or any discussion of whether or how it nonetheless respects the rights enumerated in the Charter.

The invocation of section 33 means that legislatures are wielding their elected mandate as a cudgel, not using interpretive expertise as a scalpel.

Properly understood, when we see section 33 invoked, we're not seeing legislatures say "Upon review of all the applicable principles, we think the courts got it wrong"; they're really saying "We're elected; judges aren't; and we don't care what the courts say about this."

(Indeed, the assumption that legislatures are 'interpreting' the Charter raises additional questions about whether or not there's actually a procedural obligation upon legislatures to engage with these interpretive questions: If the SCC thinks that s.33 gives the legislature the right to give effect to its own 'understanding' of the rights contained in the Charter, then does that mean that an invocation of s.33 will be ineffective without due consideration, in the legislative process, of the rights it overrides? The legislative process usually garners an incredibly high immunity to external review; this would be quite extraordinary.)

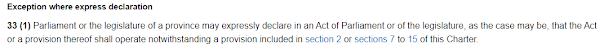

The Language of the Text

Beyond all else, 'section 33 as an interpretive mandate' is simply not reconcilable with the language of the provision itself: Sections 2 and 7-15 create substantive rights. Section 33 creates an override of the substantive rights themselves, not merely of the judiciary's interpretation of them. It allows a bill to operate as if those rights didn't exist.

When a legislature invokes section 33, they're not saying "We interpret this bill as complying with sections 2 and 7-15"; they're quite literally saying "We want this bill to operate as if sections 2 and 7-15 weren't part of the Charter at all."

No Accounting For Section 6

The notion that section 33 is abstractly about democratic primacy and allowing elected officials to have the final word ultimately fails to account, too, for the limits in its own scope, and in particular that it does not create an override for mobility rights.

Restrictions on entry and departure of citizens, and on interprovincial mobility of citizens and permanent residents, can be justified by section 1, but never by section 33. In other words, when called upon to interpret s.6 of the Charter, if the SCC finds that a restriction isn't justified, that's the final word. There's no legislative override.

Any interpretation of s.33 has to analytically account for that different treatment, and any answer that confers interpretive primacy on the legislature fails to do so.

No Effect on Judicial Interpretation

The legal tests are, and remain, the legal tests. The legislature's use of the NWC doesn't even arguably amount to a direction to the courts to modify the legal interpretive tests for Charter rights. Quite the contrary, in fact: The invocation of the NWC is time-limited and fails to even continue its own effect after a period of time.

If the legislature were really assuming a superior interpretive function, that would tend to imply that the courts should strive to give effect to the legislature's interpretation of the Charter more broadly: Well, if the legislature thinks that that law doesn't infringe freedom of expression, then it's tough to reconcile how this law could infringe it.

That doesn't happen. Which means that either the Charter rights have potentially 15 different interpretations - one for each Provincial/Territorial government, one for Parliament, and one for the judiciary - all of which are binding and correct in different contexts and on different occasions, or else what legislatures are doing isn't an interpretive exercise.

Clarity in the Public Discourse

We're regularly seeing a very cloudy discourse about the notwithstanding clause: A lot of semantic pedantism about how a government invoking section 33 can't be violating the Charter because section 33 is part of the Charter; assertions that it's inherently legitimate for elected officials to have the final say; arguments on social media about technical legal concepts; etc.

When partisans tell you that their party's invocation of the Notwithstanding Clause shouldn't be condemned because it's within their constitutional powers and they have a democratic mandate, what they're really saying is that governments should be able to trample all over the rights outlined in sections 2 and 7-15, as those rights are interpreted by the judiciary, without political consequence.

They'd rather talk about it as any other policy question - whether or not the law is otherwise a good and/or popular policy position - without having to discuss or acknowledge the ways that it may infringe important rights of various groups and individuals. Calling it a difference of interpretation allows them to pretend that the actual rights aren't being infringed.

To be clear, the rights we're talking about include:

- freedom of expression;

- freedom of religion;

- freedom of assembly;

- freedom of association;

- life, liberty, and security of the person;

- freedom from unreasonable search and seizure;

- freedom from arbitrary detention;

- the right to be informed of the reason for arrest or detention, to retain counsel, and to habeas corpus;

- the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial in a timely manner;

- freedom from cruel and unusual punishment;

- the right not to self-incriminate;

- the right to an interpreter in a criminal trial; and

- equality rights.

The populization of legal discourse is an incredibly dangerous trend: Last week, a nine-judge panel of the Supreme Court unanimously concluded (I'm paraphrasing) that a "lock 'em up and throw away the key" approach to criminal justice constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. (The alternative being to let them seek parole at some point, and assess then whether they meet the standard for parole. For most cases where that might be affected by this ruling, the offenders are unlikely to ever get paroled, but we can't rule out the possibility of a case with unusual features that breaks that mold. Particularly in the criminal justice system, we don't deny people access to a process just because we think the outcome is a foregone conclusion.)

As a result, at least one prominent CPC leadership candidate is promising to invoke the notwithstanding clause in response.

There's a reasonable discussion to be had about the proper scope and interpretation of section 12 - though a unanimous decision of the SCC usually signals that it's not all that contentious - but those who disagree with the decision aren't largely making an argument based in constitutional interpretation principles, but rather accusing those who agree with it of standing in solidarity with violent criminals. (Yes, I've seen this even from lawyers, as below.)

Even those who tend to argue constitutional interpretation from a theory-based perspective largely can still only muster pathos-based arguments against this finding. I've seen originalists - who typically argue strenuously against using public sentiment as a factor for constitutional interpretation - argue that the Supreme Court ought to have reached a decision more aligned with the views of "most ordinary people".

The fact that Asher needed to use the specific case of a "mass murderer" to speak to public sentiment is telling.

Yes, section 12 has been interpreted as integrating some sense of proportionality, in the sense that oppressive mandatory minimum sentences for relatively minor offences get struck down: A given punishment may be 'cruel and unusual' because the offence just wasn't severe enough to require it.

However, the more natural and traditional sense of the s.12 language (which you'd think an originalist would really want to look to) is decontextualized, that there are just some penalties that are completely off the table regardless of how serious the crime, and that's the sense that's being invoked in the context of Bissonnette - not that his crimes weren't serious enough to warrant the most severe penalty, but that there's a hard cap on sentence severity that applies regardless of how bad the offence was.

If we apply 'proportionality' logic to Bissonnette, that a punishment is only cruel and unusual if it's disproportionate to the crime, then I dare say that "most ordinary people" would not find any possible punishment (no matter how cruel or depraved) to be disproportionate to the severity of his crimes - in other words, that there's a threshold of severity where we cease to apply s.12 at all.

The very point of s.12 is to restrain populist impulses toward treatment of people who have committed criminal acts. If we're prepared to subject its interpretation to populist considerations, we might as well not have it.

And the same is true of other rights: Public opinion isn't known for its intellectual consistency, and people are far more likely to dismiss the significance of rights infringements that don't affect them; hence, a populist 'interpretation' of the Charter will tend to be hostile to minorities in particular - such as actual or proposed NWC invocations to restrict minority religious groups who wear religious symbols, or to restrict the rights of the LGBTQ2S+ community, or to restrict the rights of minority language groups.

Yes, the Charter is designed in a way that allows an elected government to override these rights. But if they're doing so, allowing them to obfuscate the disregard for these rights by hiding behind some pseudolegal interpretive difference dramatically increases the danger the NWC poses to liberal democracy.

My thesis is simply this: That when the government invokes the NWC, the public should understand them as saying "We understand that this law may infringe certain rights in a way that is not demonstrably justifiable in a free and democratic society, and we're doing it anyways."

Otherwise, what's the point of telling the legislature "You can ignore s.2, but you have to do it expressly", as s.33 does?

The Exceptions that Prove the Rule

There are a few cases where bills were proposed or passed in response to judicial findings that were subsequently overturned on appeal.

A good example of this is Good Spirit School Division: In 2017, a Saskatchewan judge ruled that allowing non-Catholics to attend publicly-funded Catholic schools was discriminatory. Most people (myself included) thought that was wild. (That Catholic schools are publicly funded at all is only permissible because they're specifically entrenched in the constitution, but excluding non-Catholics seemed to make it so much worse.) In response, the government introduced a bill relying on the NWC, but - moreover - they appealed it. The courts granted stays of the declaration of invalidity until the appeal was decided, and then the appeal was allowed.

In other words, the NWC (which on those facts I'd have otherwise agreed with) was entirely unnecessary.

The courts aren't perfect, but when they reach a conclusion that's clearly wrong, appellate courts usually deal with that appropriately.

Conclusion

Our fundamental freedoms, legal rights, and equality rights are not absolute. Sections 1 and 33 of the Charter make that abundantly clear: There are limits. Courts respect 'reasonably' limits; the legislature has a freer hand in limiting rights.

But when we start asking questions about how we as a society define those rights, there should be an answer. We can argue about what that answer ought to be, about the precise scope of freedom of religion, etc., but the final word on the content of those rights shouldn't be: "It depends whether you ask the Federal government, the Provincial government, or the courts."

The notion of subjectivity, that - say - wearing of religious symbols doesn't fall within the meaning of s.2(a) because your Provincial legislature says so, goes beyond simply 'limiting' the right, and removes all content from it. That's a moral relativist philosophy designed to defuse and delegitimize the moral outrage a population might rightly exhibit to serious infringements of fundamental freedoms and legal rights (etc.).

The NWC is already the biggest threat to the Charter's entrenchment of liberal democratic values, in that it permits governments to totally cast aside rights like free expression and due process.

But to go a further step and say that the NWC actually legitimizes a government's actions by claiming that a government invoking the NWC, by definition, isn't actually infringing fundamental freedoms, legal rights, etc., takes it further than it can or should bear.

The Notwithstanding Clause allows governments to infringe the rights otherwise protected by various parts of the Charter. It does not change the nature of those rights, or mean that the government's actions aren't actually infringements of those rights.

*****

Dennis Buchanan is a lawyer practicing labour and employment law and civil litigation in Edmonton, Alberta.

This post does not contain legal advice, but only general legal information. It does not create a solicitor-client relationship with any readers. If you have a legal issue or potential issue, please consult a lawyer.

Comments

Post a Comment