Employment Contract or Workplace Policy?

One of the more subtle under-explored questions in employment law is the proper difference between what employers can put into "policies" versus what kinds of changes need to be reflected in "contracts".

The central practical difference between those two things is that a "policy" is typically unilaterally drafted and implemented by the employer (so the employer can demand that the employee read, acknowledge, and abide by a policy), whereas a "contract" requires agreement by the employee (at least in theory - setting aside certain issues in constructive dismissal law).

The law is pretty clear on a couple things that can't be imposed by unilateral 'policy': The big one is 'limitations on termination entitlements'. In some cases, you can set out a contractual limit on what an employee gets upon dismissal, but trying to do that simply by way of a policy is not generally going to be effective. (Can you integrate a policy into a contract? Maybe. But it's a bad idea regardless, because changing the policy will create problems.)

It's fairly well-established that anything that the employer will seek to rely upon to govern rights and responsibilities after the end of the employment relationship - such as restrictive covenants - have to be part of the contract.

But the right of employers to impose policies is generally regarded as being pretty broad. Subject to limits associated with prohibited grounds of discrimination, there aren't a lot of recognized restrictions in terms of what kinds of policies an employer can implement. Employment contracts usually, impliedly or expressly, confer broad policy-making authority upon the employer, and require employees to comply with those policies.

Still, we should generally be skeptical of any contract that imposes obligations to comply with unspecified and arbitrary future obligations in the discretion of the other party. The proposition is broadly inconsistent with 'mutuality' as a governing principle of contract law. In the same way that we don't allow employers to assign tasks that fundamentally change the nature of the job - for instance, you can't generally add 'cleaning toilets' to the job description of your CFO, despite a broad contractual right to assign new duties to employees - I would suggest that the employer's policy-making power ought to be regarded as limited to specific contents.

The Doctrine of Managerial Prerogative

In the Union context, most collective agreements include a "Management Rights" clause which gives employers broad rights to set reasonable rules as to matters not otherwise spoken to in the collective agreement. Collective agreements are fairly comprehensive, there's a lot of arbitral jurisprudence interpreting the scope of those rights, and the relationships between employers and unions are pretty different from those between employers and non-unionized employees.

So the in-scope perception of 'management rights' doesn't fully convert to the non-union context.

The non-union analogue to 'management rights' is a 'managerial prerogative' - the flip side of implied employee duties of service and loyalty. (Demeyere points out that this is doctrinally quite broad - extrapolating all of the employer's power from the old law of master and servant, with none of the employer's duties that historically accompanied that power.)

Policy-making power is, to my mind, essentially an extension of that prerogative: A policy is simply the employer reducing a direction to writing, making it one of general application. Anything that the employer is entitled to require an employee to do, they can do by policy.

Therefore, to my mind, there's no operational difference, as between an employer and a specific employee, between the employer emailing the employee and saying "From now on, do x", versus instead implementing a policy requiring employees to do x, giving the employee the policy, and having the employee execute an acknowledgment. (Practically speaking, there's a difference in scope: The policy applies to all employees, including future hires, etc., and creates an easier record to draw upon to show those expectations. Ad hoc directions to employees can be cumbersome and problematic. The acknowledgment also resolves possible evidentiary issues, reducing the possibility of the employee later saying "I never saw that email." But what those directives do is identical.)

The employee acknowledgment of a policy, properly understood, is never contractual in nature: It is never an independently-enforceable contractual document (even if it purports to be), if for no other reason than that it always lacks fresh consideration. The employee acknowledgment is important because it evidences the employee's awareness of the policy, but the obligation to comply with policies is external, a feature of the employment relationship itself that employees are obligated to obey management directives - within limits.

When you start looking at policies as simply employer directions, as opposed to some form of unilateral imposition of new contractual requirements, the proper scope of those directions comes a bit more into focus.

The Scope of Managerial Prerogative

Let's start with the low-hanging fruit: Management is entitled to dictate the work to be performed and the manner in which it is to be performed. Therefore, employers can tell employees what to do - so long as it doesn't fundamentally change the character of their employment. They can tell employees how to perform the work, when to perform the work, where to perform the work, etc.

These are the most fundamental rights and aspect of management.

But it's broader than that, going to management's rights to oversee conduct in the workplace, and using employer assets, more generally: Dress codes, Respect in the Workplace policies, Use of Technology policies, and more.

There are also policies relating to management of the employment relationship itself - payroll processing policies, guidelines for how to request paid time off, policies for reporting sick time, disciplinary policies. These types of policies have a split purpose - partially about setting clear employee expectations for how these processes will unfold (as well as directing middle management in how to conduct them), and partially about requiring employees to cooperate in those processes.

None of these are broadly controversial.

Limits and Grey Areas

There are limits to these powers, and these evolve all the time. For example, while employers are entitled to direct where and when the work takes place, and this does extend to a right upon the employer to change office hours or office locations, that's not without restrictions.

The first and biggest limit is, again, human rights considerations. The way the law is leaning right now, my assessment would be that an employer who wants to change hours of work from, say, 9-5 to 8:30-4:30 (which ordinarily would be generally within the prerogative) probably has to give people with family obligations reasonable notice to allow them to restructure those obligations.

Next, there are limits in terms of the scale of those changes. This wasn't always true - in researching for a paper on constructive dismissal, I came across an absolutely wild case from the ONCA in the 1980s, Smith v. Viking Helicopter, where an employer relocated its operations from Ottawa to Montreal, and the employee - a long-service employee with deep roots and ties in Ottawa - didn't want to move: The Court concluded that it was reasonable to expect that the employee should be prepared to move with his job, and dismissed the constructive dismissal action. (Incidentally, this is one of a list of cases where the court attacks a straw man by denying that the employee is "entitled to a job for life" - while that's generally true, it almost never deals with the bona fides of a plaintiff's position. In Viking Helicopter, the contention isn't that he's entitled to a job for life in a place of his choosing, it's that the employer cannot require him to move to a different city as a term and condition of continued employment, and so if they want to discontinue his role in Ottawa, their options are either to negotiate a move or else to terminate the contract in accordance with its terms.)

Today, however, Viking Helicopter is anachronistic, the product of a different time. See, for example, Reynolds and Wilson. The Ontario Labour Relations Board has adopted a practice, in determining constructive dismissal claims under Ontario's ESA, of asking whether a proposed relocation unreasonably extends the employee's commute.

Further, express contractual arrangements can fetter employer discretion, as in Nufrio. So, at least in theory, if my employment contract specifies hours of work and doesn't reserve employer authority to change it, then the employer is barred from unilaterally changing office hours in a way that would change my contractually-agreed hours.

Another grey area arises where a policy compromises some other legal right of an employee: For example, I've seen contexts where employers assert some sort of rights over the employee's own electronic devices because it contains the employer's confidential information - for example, in "Bring Your Own Device" workplaces. If the employer unilaterally asserts a right, by policy, to seize an employee's device under certain circumstances, to inspect the device (including the employee's own private and confidential records), to reformat the device (deleting the employee's own personal records), etc., does that effectively override the employee's own in rem property rights in the device and their records on the device? If my employer unilaterally imposes such a policy, and I leave my phone on my desk during a meeting, is my employer entitled to simply seize the device and make whatever use of it the employer wants? If my employer demands the device, is it entitled to legally obligate me to provide it? Or to seek legal remedies for my refusal to do so? Would my refusal be properly disciplinable misconduct?

Also, returning to the proposition that policies are not standalone contractual documents, and that anything an employer can require by policy, they can also require by directive, the question of whether this is properly the subject matter of a 'policy' is a bit secondary: If they're entitled to create a policy allowing them to seize electronic devices, then by extension they would be entitled to simply seize electronic devices.

My take is that reasonable people should be very skeptical of an employer unilaterally asserting rights over employee property. This is manifestly different from the contents of most policies, and entails the employee relinquishing legal rights without consideration or assent. I would argue that this is paradigmatically outside the scope of the management prerogative: You want a right to reformat the data on your employee's device? Put it in a contract, with consideration and assent.

(Relatedly, sometimes the question arises of confidentiality. Best practice is to put confidentiality obligations into a contract, and to implement information management practices via policy, but for clearly-confidential information, I'd tend to conclude that there are confidentiality obligations implicit in the contract of employment. However, while I believe that an employer is generally entitled to the return of all its confidential records at the end of employment, I also believe that any effective mechanism for policing that obligation has to be established in contract. )

Another decent question: Ownership of intellectual property. In theory, I'd suggest that this is a matter of contract. However, because employers are presumptively entitled to intellectual property created by employees in the course of their employment, policies to clarify the treatment of that pre-existing right are usually going to be fairly safe. That said, if an employer wants to assert IP rights that go beyond the scope of that common law presumption, I'd argue that it has to be entrenched it a contract.

Or there are questions about the treatment of pre-taken vacation: Policies can clarify how vacation entitlements accrue and are applied, and a question sometimes arises where employment ends and an employee has taken more vacation time (and pay) than their entitlements to the termination date. Ontario has a fair bit of case law on this, suggesting that employers are entitled to claim vacation overpayments and offset those against other wages, but that this expectation should be made clear at the front end - i.e. by way of policy. (When you're looking at a case where vacation entitlements and deficits are closely tracked, this shouldn't generally be too surprising. But in a case where an employer is relatively lax about PTO and routinely gives an employee a few days per year over what their contract formally says they get, it'd be pretty unjust for a 20-year employee to resign and then face an employer claim for multiple months of wages back.)

Limits on Incentive Plan Payouts

But where the major grey areas arise is where policies purport to impact employees in ways with tenuous or non-existent connections to the work or the workplace - such as policies governing conduct outside the workplace and outside of working hours - i.e. in places that they don't control, during time that they're not paying me for. To what extent is the employer entitled to set policies governing what I do on my own time and in my own space? If my employer establishes a policy that prohibits me from eating pineapple on pizza, ever, is that a legitimate workplace policy? If it comes to the employer's attention that I had a slice of Hawaiian pizza at a New Year's Eve party at my cousin's house, can I properly be disciplined or dismissed for cause for that?

It's uncontroversial that there are scenarios where employers can regulate conduct outside the workplace, but they have fairly specific features: Basically, if an employee's conduct outside the workplace risks making the continued employment relationship untenable, it can be disciplinable - and, by extension, can be regulated by policy.

So if a senior executive of the company gets drunk on a plane, forces the plane to land, and ends up splashed across national newspapers the next day, the employer is thought to have a reasonable interest in addressing that. Same thing when a pilot who flew for a small airline in the Canadian Territories shared offensive posts on social media about flying in Indigenous communities.

Most people agree that these kinds of things raise legitimate employer interests and can be regulated by employer policy.

We don't all agree as to why or how. There are really two plausible theories: The 'reasonableness' approach, adopted in labour relations for management rights, that suggests a broad employer right to make any policy that's 'reasonable', or a category approach that suggests a contextually-implied term to regulate specific types of conduct based on the nature of the employee's role and the organization itself. I'll come back to this in a near-future post looking at certain practical implications of the difference.

But for the purposes of this article, suffice it to say that, when an employer is entitled to regulate out-of-workplace conduct, it's usually something that can be done by policy.

Another truly interesting controversy - one that's still getting sorted in the law, but where I believe there's a straightforward correct answer even if the courts sometimes get it wrong - is policies restricting payout conditions for bonuses: So, for example, the employer creates a formulaic policy for a bonus, with a condition that I won't get paid the bonus as part of any payment in lieu of notice: So if I'm dismissed shortly before the payout date, I don't get the bonus even if my notice period carries me past the payout date.

The Supreme Court dealt with a similar question in Matthews, as did my "Defining Wrongful Dismissal" paper (which was relied upon in Matthews), coming to the explicit conclusion that employees are entitled to get paid bonuses they would have received during the notice period, and that even had the incentive program in question explicitly deprived him of the payout in the event of an unlawful termination, it still wouldn't have been effective. (Side note: I'm not entirely thrilled about how the SCC articulated this point, but it gets to the right place.)

Put simply, in a wrongful dismissal action, we don't usually look to enforce bonus plans; rather, we're suing for the termination without notice that prevented us from being eligible under the bonus plan. If I have a stock option plan where valuable options are about to vest, and then I get dismissed just before the vesting date, I don't sue looking for stock options; I sue looking for the employer to provide me with enough cash to compensate me for the loss of those stock options.

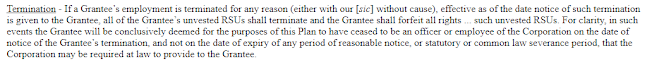

However, in the Kosteckyj trial decision (partially reversed on appeal on other grounds), the court gave effect to language in the bonus Plan that 'deemed' the employee to no longer be employed through any period of notice.

In my view, there are serious problems with this language - in particular, that it explicitly tries to avoid the application of statutory requirements. While, conceptually, the attempt to contract out of obligations during a period of actual notice - therefore being able to say, "No, had we given her actual notice, she still wouldn't have been entitled to it!" - is pretty clever, the logic extends to some pretty oppressive results, and (relatedly) it's inconsistent with most employment standards legislation in some pretty fundamental ways.

It's not clear to me whether the bonus "Plan" in that case is contractual in nature - it's referred to as an 'agreement', which suggests it may be. If we assume it was unilateral, however, then statutory issues aside, it doesn't strike me as likely permissible for an employer to 'deem' the employee as no longer being employed for any purpose in a policy, or to create a different status for employees during a working notice period for purposes of non-discretionary bonuses.

Bonuses are fundamentally contractual, and while a contract can defer a degree of authority to the employer to change the details of eligibility, payout amounts, payout dates, and even accrual rates, any non-discretionary bonus entitlements are de facto annexed into the contract of employment, and eligibility limits for amounts that would have been received during a reasonable notice period have to be built into a contract, not a policy. (A policy, otherwise compliant with the contract, that specifies that bonus entitlements are not pro-rated at the end of employment...may be more effective.)

Simplifying the Question

At its most basic, policies are ways that the employer uses pre-existing contractual rights, while contracts are ways of establishing those rights in the first place. (It's easy to gloss over the distinction, because employers have so much bargaining power that they're often able to impose contractual terms without much pushback from employees, and because courts are shockingly willing to give contractual effect to employer action that is actually unilateral - including but not limited to misreading a policy acknowledgement as contractual acceptance.)

Practically speaking, the most useful litmus test for an employer is the question of whether the point of the policy is to govern conduct during the employment relationship - so as to be able to discipline and/or fire the employee for breach - or to govern the termination of the contract or events after termination.

If the intention is simply to be able to fire an employee for not complying with directions, use a policy. Not to say that the policy will necessarily be effective for turning the conduct you're prohibiting into 'just cause', but if you're entitled to assert just cause on the basis of employees breaching a certain direction, you can make that direction by policy.

However, if the goal is to protect legitimate employer interests in ways that might apply outside the confines of the employment relationship - non-competition obligations, non-solicitation obligations, creating mechanisms to be able to verify the return of sensitive information, etc. - or to limit the employee's entitlements on termination, doing so by way of contract is likely necessary.

This is probably a slight oversimplification, but I'd suggest that the only times non-union employers should ever expect to rely on a policy in a court proceeding are either (a) in support of a just cause defence; (b) to defend and explain their own conduct - faced with allegations of bad faith and/or creation of a hostile work environment - as being consistent with their established policies; and (c) to rebut employee claims of affirmative contractual rights arising from a soft 'mutual understanding' where express contractual terms and traditional implied terms would otherwise favour the employer's position.

*****

Dennis Buchanan is a lawyer practicing labour and employment law and civil litigation in Edmonton, Alberta.

This post does not contain legal advice, but only general legal information. It does not create a solicitor-client relationship with any readers. If you have a legal issue or potential issue, please consult a lawyer.

Comments

Post a Comment