The Right to Bargain - A Primer

With the Doug Ford government in Ontario controversially invoking the Notwithstanding Clause to pass labour legislation forcing new collective agreements on school workers and prohibiting strike actions on threats of hefty fines, it's worth a look at exactly why he needs to use the NWC in this context.

There are conservatives arguing that this is all about the 'right to strike' - a right that was only recognized relatively recently (2015), and which earlier generations of the Supreme Court rejected. So the argument goes that an activist court recognized a dubious proposition, and all that the NWC does in Ontario's Bill 28 is override that new and doubtful right.

That's wrong on just about every level. Bill 28 does much more than override the right to strike, but rather overrides rights to bargain in ways that successive courts have recognized for decades. In fact, the content of its strike prohibition is so broad that it probably infringes even the earliest and narrowest interpretations of s.2(d).

Bill 28, simply, cannot be justified through deflections and intimations that it's somehow necessitated by the courts acting improperly. It is a bold trampling of well-established fundamental freedoms (among others).

Background

In the 1980s, there was a flurry of constitutional litigation in general to parse the meaning of various Charter provisions, including - most notably for our purposes - s.2(d), the freedom of association.

In what is most often referred to as the "Labour Trilogy", including the Alberta Reference, a majority of the Supreme Court of Canada adopted a narrow American-derived interpretation of the right, treating it as an individual right, rejecting it as establishing a fundamental freedom to engage in union activities or to strike.

There's good reason to think that this was an unduly narrow interpretation - that even in the 1980s, the language of 'freedom of association' within the Canadian context was understood as protecting the rights of labour. The Woods Task Force Report, in 1968, recognized that "Freedom to associate and to act collectively are basic to the nature of Canadian society and are root freedoms of the existing collective bargaining system....Collective bargaining legislation establishes rights and imposes duties derived from these fundamental freedoms."

Furthermore, even at the time, international labour law principles recognized that Freedom of Association lay at the heart of labour activities.

So even if one subscribes to an 'originalist' philosophy of interpretation, and under any model of that theory, there's every reason to believe that the intention and understanding at the time would have been that the inclusion of freedom of association protected labour rights.

The Trilogy

In Alberta Reference, a majority decision authored by Justice McIntyre* relied on First Amendment interpretation (which, notably, does not include a freedom of association) and narrowly construed s.2(d) as protecting three types of activity: The freedom to join with others in lawful common pursuits and to establish and maintain organizations; freedom to engage collectively in activities that are constitutionally protected for individuals; and freedom to pursue with others whatever action an individual can lawfully pursue individually.

In other words, Justice McIntyre's interpretation was that s.2(d) did not protect any particular substantive activities, but merely stood for the proposition that otherwise-lawful activities could not become unlawful merely because they were being pursued collectively. It's the right to collectively exercise individual liberties.

Chief Justice Dickson, in dissent, called the majority approach "legalistic, ungenerous, indeed vapid."

He argued that reliance on the American approach was misplaced: Because freedom of association isn't explicitly mentioned in the US Bill of Rights, its scope is referential and derivative of other rights: That the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech must apply not only to individuals but also to groups acting in concert.

Rather, in the Canadian context, freedom of association was long understood to be the underpinning of Canada's robust collective bargaining framework; its inclusion in the Charter had to be understood as protecting collective bargaining rights.

However, McIntyre's majority held the day, and for 14 years, union activities were without any meaningful constitutional protection.

Interbellum - Ontario Sets the Stage for Dunmore

In 1990, Bob Rae's NDP won a majority government in Ontario. One of the many changes it introduced was extending collective bargaining rights to farm workers. While the controversy on this largely surrounded the impact on the 'family farm', the practical and legal impact tended to surround mushroom farms, which are much more industrial settings than most agriculture.

In 1995, the Mike Harris PC government sweepingly reversed the NDP changes, including pulling all collective bargaining protections for agricultural workers. Attempts to unionize these workers came to a screeching halt as employers stopped recognizing or bargaining with their unions.

Critically, this was a private sector issue. The government wasn't directly telling workers that they couldn't unionize, but was telling employers that they didn't have to recognize unions.

A Right to Bargain Emerges

In 2001, the Supreme Court of Canada released a decision in Dunmore: Finding that the revocation of bargaining rights from farm workers created a 'chilling effect' - in effect discouraging employers from recognizing unions - the Court found that it was an interference with the rights of the workers.

The majority decision was signed off by seven of nine justices. Justice L'Heureux-Dube argued, in concurring reasons, that the majority didn't go far enough. Justice Major alone dissented.

The content of the Dunmore decision was narrow: Basically, the agricultural workers were entitled to make collective representations to their employers, and the employers had an obligation to receive and consider those representations...but the court didn't go further at the time. It was a landmark decision in the sense, however, that it expanded s.2(d) to include some 'right to bargain' content. Its scope would be later argued and expanded.

In 2007, the Supreme Court of Canada decided the case of BC Health Services, and took it a step further. This case involved the BC government enacting legislation allowing it to unilaterally reorganize labour management in its unionized health sector, effectively overriding negotiated terms of collective agreements.

In principle, BC Health Services was significant for recognizing that s.2(d) protected a full-fledged right to collectively bargain. On its facts, it clearly signalled to governments that they couldn't simply run their unionized workforces by legislative fiat. (Six of seven justices formed the majority in this case.)

Then, in 2015, in Saskatchewan Federation of Labour, the Supreme Court (in a 5-2 majority) expanded their approach to recognize a constitutional right to strike.

Remarkably little has changed since then: We know that the constitutional right to strike is subject to 'reasonable limits', per s.1, and we reasonably expect that these limits will justify 'no strike' laws that persist during the course of a collective agreement, or mandatory ADR mechanisms for some classes of essential government services.

Bill 28

While Ontario's Bill 28 is being spun, in some circles, as being 'back-to-work' legislation, the 'no-strike' provisions in it are secondary.

Bill 28 does a bunch of things, but the first thing to understand is that it legislates collective 'agreements'. (I put 'agreements' in quotes because, well, these are terms being legislatively imposed and not being 'agreed' to in any way.) It also nullifies any local terms that limit the employer in its ability to manage attendance.

To the extent it terminates and bars any strikes, that's not actually that unusual - with a couple exceptions, that I'll come to - because it's almost automatic by virtue of a collective 'agreement' coming into effect. The penalties for unlawful strikes, however, are more onerous than unusual.

It invokes the Notwithstanding Clause, but not only in respect of section 2(d). All of section 2, all of section 7, and all of section 15. It also excludes the operation of the Human Rights Code and the Rights of Labour Act. A significant block of the bill is about conferring all forms of immunity against the government and its agents against civil actions, unfair labour practices, human rights complaints, and other types of proceedings.

The problem is that the breadth of the strike prohibition means that there's a wide range of circumstances where workers are being effectively mandated, on threat of prosecution, to perform duties under a contract that's been legislatively imposed on them.

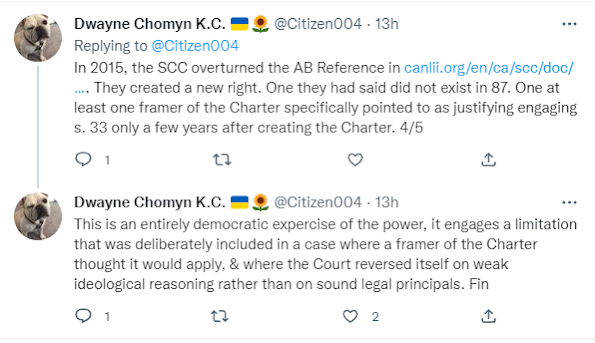

So while some people, like Dwayne Chomyn, argue that the use of s.33 here is justified by the courts overstepping in SFOL - the court recognizing a right to strike on "weak ideological reasoning", the reality is that s.33 isn't just avoiding SFOL.

Arguing that Bill 28 infringes s.2(d) would have been academic following BC Health Services, 15 years ago. It probably would have been a solid argument following Dunmore, 21 years ago. There's even an argument that the breadth of the strike prohibition engages Justice McIntyre's very limited view of s.2(d), prohibiting otherwise-lawful conduct just because it's done in association.

(It's worth noting that, since 2001, until now, nobody has invoked the NWC to limit labour rights.)

The bottom line is that if you're interpreting s.2(d) in a way that Bill 28 doesn't infringe it, you might as well just put white-out over the clause.

Doctrines of Charter Interpretation

But there's another part of Chomyn's argument that's worth noting - that Peter Lougheed indicated that he'd have used the NWC if the Alberta Reference had gone the other way, and therefore, because Lougheed was a 'framer of the Charter', we should give that weight.

No serious constitutional scholar would endorse that perspective. The 'intention of the framers' is a largely-debunked myth of American originalism - even American originalist scholars don't really buy into a "Look, here's what James Madison would have said" view of their Bill of Rights anymore. And if it was, looking to Lougheed for support on your interpretation of what s.2(d) was thought to protect is pretty weak, because he was opposed to the Charter in a broader sense.

Peter Lougheed was a member of the 'Gang of Eight', which proposed a simple patriation without the Charter. In a 'kitchen accord' between the AGs of Canada (Chretien), Ontario (McMurtry), and Saskatchewan (Romanow), the notwithstanding clause was agreed to as a compromise.

There's much more support for an 'intention of the framers' argument that supports Chief Justice Dickson's dissent, than Justice McIntyre's majority. (As well, given that modern originalists now look at 'original public meaning' instead of what some specific individuals may have thought, I'll go further to highlight that, outside the specific context of the interpretation of the US Bill of Rights [which doesn't mention freedom of association], freedom of association was generally recognized at the time as protecting collective bargaining activities.)

But the even more looming problem with trying to rely on the intention of the framers, in the context of the Canadian Charter, is that it's inconsistent with the history of Canadian constitutional interpretation, and, for good measure, inconsistent with the intention of the framers. When Chretien testified before a Special Joint Committee on the Constitution in 1981, and he was asked on his view of whether Charter rights might be interpreted in a certain way, and his answer was that it would be up to the courts. Quite consistent with the prevailing 'living tree' doctrine, he'd assembled a document with lots of vague and undefined terms, and took the express position that it was the job of the judiciary to interpret them.

I've written about originalism before. Trying to figure out 'what freedom of association meant in 1982' is something of a red herring, because its meaning didn't materially change - not from 1968 with the Woods Task Force Report, to 1982 with the implementation of the Charter, to 1987 with the Alberta Reference, to 2015 with SFOL, to today. We can look at the Woods Task Force Report, or applicable publications from the ILO, and draw a reasoned conclusion that the language of 'freedom of association' includes collective bargaining rights. There's nothing about the usage that should raise a flag on whether there's something anachronistic or temporally inappropriate about that usage.

The Notwithstanding Clause Itself

So, having established that the courts, on good grounding, have held for decades that it's a 2(d) infringement for government to legislatively limit collective bargaining rights, we come back to the more abstract question of 'what justifies the usage of the NWC'?

At it's simplest, the use of the NWC is generally a tacit admission that (a) the courts may find that the law infringed Charter rights and (b) the courts may conclude that the infringement is not demonstrably justifiable. If you genuinely believed you could convince a court that it's not an infringement, or a justified infringement, you wouldn't need the NWC.

And as much as legislatures may try to justify the NWC by challenging the merits of the courts' interpretation, the reality - as I've pointed out before - is that constitutional interpretation is the job of the judiciary, not the legislature. Trying to undermine the courts' authority in that respect - to claim "this law doesn't REALLY infringe fundamental freedoms, despite what the courts think" - is an attack on the separation of powers.

I don't question that legislatures have the power to override fundamental freedoms. The NWC doesn't have strings attached. But for proper democratic accountability, we need to recognize its use in light of the fact that the legislature has an unfettered right to override those Charter rights, and that - if we place any value on our fundamental freedoms, etc. - we should be deeply skeptical when a government chooses to do so.

In Bill 28's invocation of the Notwithstanding Clause, we need to understand them as saying this:

We understand and acknowledge that this Bill unreasonably infringes fundamental freedoms, equality rights, and the right to life, liberty, and security of the person. But we think the policy we're pursuing - of keeping these workers at work without being required to reach an agreement that they work voluntarily - is more important than those rights.

All arguments to the contrary, including Chomyn's, all hinge on a fundamentally circular argument that it's okay to invoke the NWC simply because their powers include the NWC. There is no case, no hypothetical legislation, where that logic - if accepted - would cease to apply.

The important thing about these entrenched rights is that, while there can be reasonable context-based justifications for infringements under s.1, we as voters are very poorly-equipped to assess justification for ourselves. There's a deep-rooted temptation to forgive rights violations that don't affect us, on policies that otherwise appeal to us. But if we give into that temptation, then our entrenched bill of rights ceases to have any meaning. If we're okay with ignoring the freedom from cruel and unusual punishment for criminals we don't like, with ignoring free expression for political expenses we don't incur, with ignoring bargaining rights of unions we aren't part of, then we're effectively telling the government that we don't really care about the infringement of Charter rights so long as we otherwise like the policy being pursued, and so long as the Charter infringement doesn't impact 'us'.

Conclusion

Does Doug Ford have the power to disregard fundamental freedoms? Yes, almost certainly.

But let's not indulge any pretense by conservative apologists that Bill 28 doesn't actually do that. He's dictating terms to workers, in spite of their constitutionally-entrenched fundamental freedoms otherwise, because he can.

This is an oppressive and abusive piece of legislation, that walks all over Charter rights of low-paid workers to avoid paying them a fair wage. Everything else is just a deflection.

*****

*Correction: Justice McIntyre wrote a solo concurrence, not the majority reasons. In fact, there was no majority in the Alberta Reference. Six judges took part in the decision: Beetz, Le Dain, and La Forest joined with McIntyre in the result, but their reasons were separate and cursory. Dickson and Wilson dissented.

Dennis Buchanan is a lawyer practicing labour and employment law and civil litigation in Edmonton, Alberta.

This post does not contain legal advice, but only general legal information. It does not create a solicitor-client relationship with any readers. If you have a legal issue or potential issue, please consult a lawyer.

Comments

Post a Comment