A Word on Electoral Reform

Every election time, we have debates about strategic voting and electoral reform. With the unusual recent result in Ontario where the Ontario Liberals and NDP scored equal numbers of votes, but with vast disparities in resulting seat counts, it's even more striking.

Our oddly-named "first past the post" (FPTP) system has some pretty deep and obvious flaws, and is unpopular, but we're far from consensus on how to replace it.

The two central proposed replacements are 'ranked ballots', where you can select 'second' and 'third' choices on your ballot (which I'll call IRV, for 'instant runoff voting'); and 'proportional representation' (PR), which allocate seats based on vote percentages. However, there are as many different types of PR system as colours in the rainbow.

There's a large undercurrent of support for PR as a concept, but you don't see a lot of people getting into the nuts and bolts of the model they want. Every election, you see people start talking about "With PR, the seat count would look like this". Setting aside that different electoral systems change campaigning and voting behaviours in a range of ways (we'll come back to that), this assumes a very particular, very pure form of PR, which I've never seen any PR advocates actually stand behind.

Because it's a deeply flawed system.

Any time you start talking about the flaws in PR, you get advocates saying, "Sure, but there are options that don't have that problem." The range of systems is wide, sure, but the nature of the issues is such that it's kind of like trying to smooth bubbles in wallpaper: You smooth it out in one spot, and it just pops up in another.

So let's talk about it.

The Problems of FPTP

First, let's talk about the issues we're trying to fix in FPTP.

There are basically two issues raised by this system: The first is a split vote, where slight disagreements over policy are as impactful on electoral outcomes as fundamentally different ideological worldviews.

To oversimplify the point, imagine that 75% of the population wants to fund a public transit system, but they disagree on the details: 15% want LRT; 15% want traditional buses; 15% want subways; 15% want a hybrid network; and 15% just absolutely insist that the transit worker dress code HAS to be plaid. So five different parties form representing these five different options. Under FPTP, the 25% of people who don't want a public transit system at all have a plurality, and so - despite a supermajority agreement that policy action is necessary and appropriate - the minority wins.

This is inarguably a problem, allowing minority groups with broadly unpopular positions to take power. I've never seen anyone seriously defend this outcome as having any meaningful silver lining.

Within the FPTP system, this drives strategic voting, looking at who has the best chance of winning and voting for your favourite of those. (To be clear, when I'm talking about strategic voting, I'm talking primarily about riding level assessments as to who will win. Strategic voting based on Provincial/National poll numbers is almost always ineffective and often counter-productive.) Strategic voting, to the extent it is used, helps correct the 'split vote' issue, but at a cost: It suppresses the divergence of voices within an ideological camp, forcing an artificial consensus.

More formally, sometimes you actually get party mergers to overcome the problem of a split vote, as with the former Federal Progressive Conservatives merging with the Alliance to form the CPC, or the Wildrose and Alberta PCs merging to form the UCP. This is more effective than informal strategic voting, but - as we've seen - it significantly exacerbates the tensions within those camps.

The second issue sometimes raised by FPTP - which is not strictly a consequence of the voting system but more a result of the representational model we use - is that it effectively ignores 'unsuccessful' voters: Even in a case where a person gets 51% of the vote, that leaves 49% of voters in the area without representation satisfactory to them.

Thus, you can get scenarios where a party like the Greens gets (for example) 10% support across the board, but only converts it to <1% of the seats (or sometimes NONE). The argument is that it feels unjust to those 10% of voters, like they're somehow unrepresented in the legislature.

Strictly, our model means that representatives are, at least in theory, accountable to their entire constituency. In practice, there's a tendency, especially in some groups, to cater only to the groups targeted to secure re-election. (From a 'legislative policy' perspective, this is kind of a natural consequence: If I run for office, I'm targeting a plurality of voters that hopefully shares my values and priorities, and as a matter of policy and platform it only makes sense that I will prefer those issues over those of the smaller minority that failed to elect their preferred candidate. But from a 'consultation' and 'service' standpoint, we should expect and demand that all constituents have generally equal access to their representatives, and that doesn't always happen.)

When I was much younger, I believed that the 'geographical representation' model was outdated and had no relevance to 21st century Canada. Having lived in many different types of environment (rural communities, major cities, suburbs) in different Provinces, my thinking has evolved and I can say categorically that this was wrong: Different communities have materially different interests and priorities that require local representation.

So while I'm certainly sensitive to the argument that third parties are stifled by FPTP (in the sense that people are inclined against voting Green because it's not strategic), I'm no longer personally convinced that it's a problem that a party with 5-25% support in a community doesn't get representation in respect of that community.

IRV - Instant Runoff Voting

Instant Runoff Voting is one of the 'simpler' modes of electoral reform: Instead of checking one box, you rank candidates in order of preference. (There are other models that allow you to simply check multiple candidates without prioritization, but the problem that seeks to address in IRV is pretty small, and it brings its own challenges.)

So in the first count, you just look at 'first preference' ballots, as in a FPTP election: If one candidate gets 50% + 1 of first preference votes, then that candidate wins, and the count ends. If nobody reaches that threshold, however, then you eliminate the candidate with the fewest votes, take the votes from that pile and add them to their second preference candidates. If that doesn't push a candidate over 50%, then you eliminate the new 'last' place candidate, and so on.

This entirely solves the problem of vote-splitting, and mostly cures strategic voting as we understand it. In a 3-party system, where you have clear preferences of first, second, and third choice, there is no down side to casting your first preference vote for your favoured choice, and then give second preference to the 'lesser evil' of the other two.

IRV does not seek to fix the problem that opposed voters are supposedly left unrepresented. However, it does reduce some of the impacts.

Firstly, it impacts campaign behaviour: While FPTP incentivizes politicians to cultivate a plurality who will vote for you, and who cares what everyone else thinks, in IRV the opinions of non-supporters matter. That breaks outside of current 'tribal' attitudes that you should only pander to and motivate your base, because if you're not at least making yourself palatable to a clear majority of voters, you can't win.

In this way, IRV rewards campaigns and policies that have broader majoritarian appeal, and punishes policies that energize the party's base but infuriate everyone else.

Secondly, it removes the obstacle to third-party voting. You no longer get the artificial suppression of third party voices by the practical reality of a two-party race. Without a Green vote being 'thrown away' in most ridings, IRV removes a significant obstacle to them being taken seriously, and in the long term promotes a more robust multi-party political dialogue.

Preferential ballots are used in various contexts. They have occasionally been used Provincially in Canada, and are used by many political parties to select their own leadership - including all major Federal parties, including the Green Party of Canada. London, Ontario, has shifted to it for municipal elections, and other municipalities are making that shift.

Internationally, it is used for the Australian House of Representatives, for by-elections to assemblies in Northern Ireland and Scotland, and in certain US State and local elections.

PR Systems

At its core, PR is intended to cause the makeup of a legislature to match partisan support in the election - so in theory, if one party gets 25% of the vote, they should get 25% of the seats.

This 'pure' PR raises all sorts of problems, including:

- In a legislature with hundreds of members, fringe and single-issue parties can gain legislative power on the basis of less than 1% support.

- The proportion of votes will almost never break down cleanly into a number of seats. Remainders and rounding issues need to be accounted for.

- When you're voting for a party instead of an individual, the party gets to decide who to seat in the election. That means that the legislators themselves are accountable to the party and not to the electorate. (This goes beyond what 'party discipline' does.) This means:

- No local representation or voices speaking to local concerns;

- Limited potential for dissent and disagreement within the party;

- No particular person or set of people who have a specific mandate to speak to the interests of any constituent;

- Independent voices are institutionally suppressed; etc.

Sure, if 10% of voters support a party and don't get representation, that's an undemocratic travesty, but if it's only 4.9%, who cares about that group, right? This is the first break in the 'compromise' PR systems: You cannot simultaneously believe that a person's vote not applying toward the election of a representative is unjustifiably 'undemocratic' while also agreeing that it is justifiable to suppress parties that fail to achieve a certain threshold.

The second issue means, inherently, that some ballots have to be disregarded. In a single national PR system electing hundreds of roles, that's going to be a small number of ballots by any method - in Canada, for instance, one seat would correspond to less than a third of a percent support, so the rounding issues are small. However, if you start looking at models of multi-member proportional constituencies - where you're picking a handful of seats for a region - those numbers suddenly get much larger.

The third issue runs deeper, and tends to be addressed through a proposal known as "STV" - single transferable vote. This is, at best, a semi-proportional system hybridized with a preferential ballot.

Single Transferable Ballot

Basically, this model retains some semblance of geographical representation, but with constituencies that elect multiple members. So, for example, in the Republic of Ireland, each constituency has three or more members representing it: So if you have a three-member constituency, then you tally the number of votes cast, calculate a quota (the number of votes necessary to elect a candidate), and then if a candidate reaches that on first preference ballots, excess votes are distributed in accordance with their second choices. (It still uses an IRV-style mechanism for eliminating 'less' popular candidates.)

There are a few things to highlight about this system, generally:

Firstly, it does not, in fact, result in a proportional outcome. In the last Irish election, for example, the party with the most first preference votes was the Sinn Fein; the party with the most seats was the Fianna Fail. It also doesn't eliminate the phenomenon of wasted ballots: For meaningful numbers of voters (lower than in FPTP, but still usually double-digit percentages), their vote still doesn't actually help elect anyone. And remember that we're talking about counting people's fourth, fifth, or sixth choices, which still don't ultimately do anything.)

Secondly, it doesn't effectively create a threshold of any sort: There are five parties represented in the Dáil Éireann with less than 5% support. And three of them have potentially meaningful power. In theory, any one of the three could help the two parties with the most seats pass a bill. In practice, since the Sinn Fein tends to be more of a political outlier, the passage of most contentious bills will require sign-off by the first and third place parties (by seat count), bolstered by some other combination of other parties. The Greens - with a modest 7.1% of the popular vote, were the only party capable of individually turning the Fianna Fail and Fine Gael into a governing coalition, and in practice that turned out to be the only viable option - giving the Greens' 7.1% an effective veto on the formation of a government. That's a lot of power for a small group.

Thirdly and relatedly, particularly at the low end of support bases, it can have wild swings in representation depending on vote efficiency - despite the Social Democrats getting only about 2/3 the votes of Labour, both parties got the same number of seats.

This is all a function of the fact that seats are still distributed on a geographical basis, meaning that 'vote efficiency' still has a great impact. The Aontu party got one seat in Meath West. Across Ireland, it received about 40k first preference votes - but about 7k of them were in Meath West, and on the sixth preference (in a contest to elect three out of nine), they managed to beat the quota.

What this means is that a party with an even 10% support nationally may not get a seat, but rather getting a seat still depends on getting a concentration of support in a local riding (as in Meath West, where 10k out of 40k voters agreed that the Aontu guy was not the absolute worst). The quota system means it's easier for non-mainstream parties to break into targeted ridings than in either FPTP or single-member IRV, but how much easier depends more on the concentration than the size of their support base.

The result of a system like STV is that, as in FPTP, a party wants to target its core base, and be 'palatable' to a relatively small group outside that. Like FPTP, it encourages politicians to target a minority, and to not care if the majority in a region despises them. In fact, the minority they really need to target is even smaller in STV.

This means that local fringe and single-issue groups are likely to get representation, and more easily, often, than alternative parties with broader national appeal.

STV in the Canadian Context

Let's start with a serious question about how multiple-member constituencies would work in Canada. In a place like Toronto, it's pretty easy to imagine consolidating 3-5 districts and putting 3-5 Parliamentary seats up for grabs in that area. When you get outside of urban areas, on the other hand, it's a different story: Each Territory has only one riding, and the northern ridings in most Provinces are massive. (About half of Alberta, geographically, is within maybe three ridings. The northern half of Saskatchewan is one riding. And roughly the northern three quarters of Manitoba are one riding. Nor are Northern Ontario or Quebec much different.)

So if you want to create multi-member constituencies in a way that's reasonable for the Canadian context, without further compromising our already-strained 'local' representation in certain contexts, you basically need to increase the number of seats in Parliament, multiplying it by however many members you want per riding.

Want four members per riding? Roughly 1352 MPs in the House. That would make the House the most populous legislative body in the world outside of China. (Slightly less than the total in the two UK chambers, but if you add our Senate to it, we'd still come out on top.)

So...that's a lot.

The more members per riding, the more 'proportional' the House is going to look overall, but the lower the threshold for regionally-concentrated fringes to gain representation. Fewer members invert that.

Particularly given the regionalist movements within Canada - sovereigntists in Quebec and Alberta - an STV system would very much strengthen such movements and give them meaningful influence over government policy based on the support of regional fringes.

Expectations of the Different Systems

PR Purism

The more 'proportional' the system, the more likely it is to award and institutionalize 'power' - in the form of a number of seats in perpetual minority government contexts - to groups who earn votes from fringe minorities and/or single-issue voters.

Whether or not the 'fringe minority' side of that is bad depends on your worldview. The premise of PR, after all, is that voters outside the mainstream deserve to be heard, too. But in Canada we should remember that it's not just Greens, but the PPC too. Not just people who want more progressive change than what conventional parties have brought to bear, but also white nationalists.

However, the 'single-issue voters' present another problem. Imagine if a party campaigns solely on stopping immigration, draws 6% nationwide, and gets 20 seats as a result. No other economic platform, fiscal platform, foreign affairs platform. No broader interest in governing well, and no goal or expectation of EVER forming a government - just a single issue and the plausible hope that, with the right seat distribution, its 20 seats might be enough to allow an effective veto on a budget unless significant concessions are made to that singular issue. That gives a disproportionate amount of power to a small minority of people (it's undemocratic), and it doesn't foster good government.

Within a real PR system, the goal of a party isn't to build a consensus that appeals to a broad stream of Canadians, but rather to develop and speak to your own niche of support in order to maximize the leverage of their voting power.

So expect parties to focus on their base, on promoting turnout in their strongholds, and minimizing outreach to communities that are less supportive. Conservative politicians would almost never set foot in cities; Liberal politicians would almost never set foot outside them. Also expect a lot more fighting between parties of similar ideologies than different ones: NDP wouldn't target Conservative support; they'd target Liberal support.

As well, PR in this form - or any form that uses lists - strengthens party discipline. If you're premising your representational model on the idea that people have voted for the party (and not the individual), and therefore the party should obtain a corresponding degree of power, then you're delegitimizing any individual representation by the elected MPs, and MORE strongly binding MPs to follow the dictates of their leader. (Yes, under the status quo, people significantly vote along party lines, and that already leads to an environment where MPs feel beholden to the party. But that's a problem, and the fix for it is to empower MPs, not to eliminate or weaken the little power they still have.)

STV

Since the conversation seems to be built around this intellectually dishonest dichotomy of 'helping minority parties without helping fringe parties', let's talk about how parties are affected by STV.

The short answer is that it's easier (and more beneficial from a fundraising perspective) for a party to focus on winning the second and/or third seat in a riding where they already have significant support, as opposed to trying to reach out to win a first seat in a place where they have limited support. Parties will turn to their bases and strongholds to try to maximize the power come out of those areas.

Institutionally, majority governments will be essentially out of reach for everyone - so, to that extent, it sort of hurts the LPC and CPC.

The result is that neither the LPC nor CPC will continue to seek to be 'big tent' parties, instead trying to cultivate stronger support among more specific demographics. (The CPC, because of their tendency to get 'blowout' results in certain areas, will probably be better at this...but to be fair, the Liberals simply aren't attempting blowouts in a system that doesn't reward blowouts, so we can't rule out a capability of them pivoting successfully.) The NDP will struggle to maintain seat percentage in light of those concentrated efforts, but will still have a significant seat count that gives them leverage in minority governments. The Bloc will be much more secure - this insular model is really ready-made for them - and non-mainstream parties like the Greens and PPC will be able to focus regional efforts to get meaningful seat counts: When you can get a seat, at times, based on being the fourth choice for a quarter of the locals, that's a low bar.

Don't expect the LPC and NDP to generally have enough seats combined to be able to pass bills without the support of at least some other parties. The fringe parties will often have power. That's the point.

In short, STV would force all parties to close in on their own bases, trying to maximize the power generated by their strongholds with a 'small-tent' approach with negligible outreach, and then actually getting bills passed would require legislative compromises based on political expediency, putting power into the hands of smaller and more extreme fringes who can hold up legislation unless their demands are satisfied.

IRV

Preferential ballots make for a much smaller change. They don't seek to change the core of the representational model, where each legislator is the sole representative and person accountable to a local geographical constituency.

But in terms of impact, it makes it much more important for these local representatives to try to build bridges within their ridings. In a close race where the top two candidates both have ~35% support, the difference isn't going to be made by which candidate can get a few more of their voters to the polls, or can convince a few extra voters to support them; the difference is going to be made substantially by how the other 30% of voters feel about each of them. If I have 34% first preference support, and you have 36% first preference support (so you'd win in FPTP), but most of the other 30% hate you and are indifferent to me, that means I win under IRV.

They can't just pander to their base; they need to try to satisfy non-supporters, too. The electoral 'ground game' - trying to identify supporters and get them to vote - means that a politician may actually be incentivized to try to encourage non-supporters to vote in some contexts. (For example, in a two-way race between the Liberals and CPC, in a riding where the NDP isn't pouring a lot of resources, if an NDP voter needs a ride to the polls, IRV gives the Liberal campaign a strong incentive to make that happen. Which is just wild, when you think about it - a party using GOTV resources to get non-supporters to the polls? What a world that would be.)

On the flip side, it also means that parties are less beholden to their own fringes: Unlike the status quo, where parties like the CPC and UCP need to placate particularly far-right groups to prevent vote loss or splinter to far-right parties like the PPC or WIP - not because they're afraid to lose to those parties, but because loss of votes to those parties makes them less likely to beat their *real* rivals. When you get a fringe telling the CPC "Address our priorities or we'll go to the PPC", the prudent decision-making process within the CPC would be to recognize that the PPC won't generally compete with them for first-preference votes, that they will be the second preference of most PPC voters regardless, and that the election is really won or lost in the middle, competing against the LPC for higher preferences among moderates.

So the system encourages parties to take more of a conciliatory 'big tent' approach, but at the same time it ALSO doesn't force irreconcilably divided parties to stay together to avoid being decimated by a split vote. It doesn't punish the creation of a splinter party by rewarding their enemies for the splinter party's success.

If we had preferential ballots in Canada in the 1990s, the Reform and PC parties would both exist today. Within the conservative-leaning ridings, the Reform would probably do better among first-choice voters, but the PCs would generally get more second-choice votes from Liberals. But in moderate ridings, the PCs would be far better able to compete for centrist votes against the Liberals, while counting on a high number of second-preference votes from reformers.

To some extent, Australia shows such a splintering - with several parties regularly represented, plus a significant contingent of independents. Australian conservatism has split into formally different parties who operate as an enduring coalition targeting different constituencies.

Now, there's some argument that IRV makes it harder for peripheral voices to be heard, and that's arguably true to a limited extent, in the sense that outsider candidates need to get broader - if softer - support, requiring a majority of voters to check their name somewhere on the ballot, as distinct from potentially getting elected with a mere 35% or so of votes (which must be first choice) in FPTP.

I disagree with this assessment, and I don't think the real world examples bear it out: Alternative viewpoints get help from a bunch of different sources. Electorally, they're assisted by the facts that (a) strategic concerns no longer artificially suppress their support, so it's easier to listen to and take seriously an alternate voice without worrying about whether it may split the vote unfavourably; and (b) they don't necessarily need that many first-choice votes. There are examples in the Australian experience where someone outside of the mainstream powers (like Labor or the Coalition) may come in second or third among first preferences, but ultimately prevail on subsequent preferences.

Beyond the strictly electoral advantages, it also brings alternative voices into the public dialogue and strengthens them, even in local races that are fundamentally two-party affairs, by forcing even the mainstream parties to vie to be preferred by non-supporters over their mainstream rival.

Finally, by removing strategic concerns, IRV creates an environment where independents have greater potential for electoral success - which, in turn, weakens party discipline. In nearly every case, when a person leaves or is ejected from caucus and runs as an independent, they lose. This is significantly informed by strategic concerns: In an environment where it is broadly accepted that a party nomination is necessary to win a seat, voting for an independent incumbent is regarded as throwing one's vote away.

So IRV mostly cures strategic voting and improves local accountability, without fundamentally altering the nature of our relationship with our elected representatives.

Other Systems

As I mentioned earlier, there's a wide range of options. Some systems are hybrid, like Italy's mixed system that uses FPTP for part of its legislature and PR for the rest.

I fail to see the appeal of these compromise systems. The result, in Italy, is a legislative assembly that is not proportional, that fails to effectively maintain local representation, and that entrenches fringe party power while giving them a greater prospect of seizing government. It is, in short, the worst of all possible worlds.

However, it's worth being aware of these mixed systems, because there are plenty of Canadian studies that come to the conclusion that they're the right approach for Canada, and it's important to understand why.

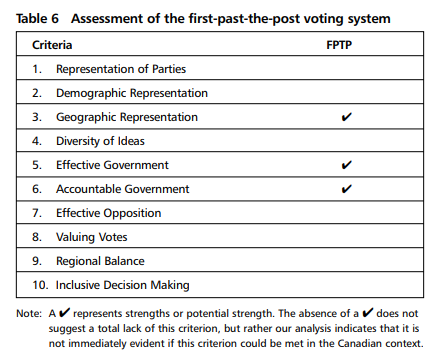

Take this study, for instance, by the Law Commission of Canada: They begin by acknowledging the problems of FPTP, concluding that of ten important metrics for gauging electoral systems, FPTP only satisfies three, and therefore needs to be changed.

Then they go on to examine four alternatives - specifically 'two-round' voting, AV (what we've been calling IRV here), STV, and list-based PR. They reject all four as not being appropriate to a Canadian context.

Two-round voting is onerous. (To my mind, it has no advantages over AV/IRV.) AV, the study concluded is better than FPTP, but fails to address the 'wasted vote' concern. STV's disadvantages particularly include "departure from the constituent-Member of Parliament principle". List-based PR is a significant departure from our Parliamentary tradition and strengthens the roles of parties.

(It's surprising and a bit disheartening that the consideration of these alternative systems is so brief. In a 200 page report, they spend under 5 pages actually looking at these. AV in particular is just a couple of paragraphs.)

And therefore, because FPTP is bad, but none of the alternatives are adequate, the Law Commission determines that a hybrid system must be the right one.

Having decided in cursory fashion that list-based PR should be dismissed because it erodes our tradition of having decisions made based on local representation and strengthens parties, the report goes on to suggest an MMP system that uses party lists to fill large numbers of seats from party lists disconnected from local representation. It certainly has the effect of diluting the power of MPs representing their constituents, and of strengthening the party.

Most studies look at the impact of a given system on a given election, and I hesitate to do that because different systems cause parties to campaign differently and cause voters to vote differently, but if we look at the 2021 election under something akin to the LCC's proposal, and assume that everyone's party vote would have been for the same party as their local vote...then today we would have a 507 member Parliament (which is quite large), with the following breakdown:

- LPC: 160 locally elected MPs, 6 MPs from the LPC list. (166 total)

- CPC: 119 locally elected MPs, 53 MPs from the CPC list. (172 total)

- BQ: 32 locally elected MPs, 7 MPs from the BQ list. (39 total)

- NDP: 25 locally elected MPs, 66 MPs from the NDP list. (91 total)

- GPC: 2 locally elected MPs, 10 MPs from the GPC list. (12 total)

- PPC: 0 locally elected MPs, 26 MPs from the PPC list. (26 total)

(Yes, that only equals 506. There are some rounding issues to be resolved differently depending on exactly how you do the math. Anyways, that's the rough structure of what we'd look at. This also assumes national proportional allocations, which is probably not what we'd be talking about. And this turns out to be a vast difference in impact, in a way that PR advocates gloss over when talking about national numbers. We'll come back to that later.)

The LPC and Bloc would be (relatively) closely beholden to their constituents, but every other party leader would have a significant base of power derived from party-selected appointees - people who are seated for no other reason than that they're picked by the party. (Okay, to be fair, there are different options for how to structure lists, but I regard it as unrealistic to assume that - regionally or nationally - voters would have enough information about list candidates that there's a meaningful open democratic process going into which 66 NDP candidates are picked off the list.) For the CPC, it's about a third of their overall caucus, but for everyone else it's an overwhelming majority of the caucus. For the PPC, it's their ENTIRE caucus. You'll excuse me if I'm uncomfortable with the idea of seating Maxime Bernier and 25 of his best friends based on the votes of a small extreme fringe.

But even for the LPC, it still consolidates more power in the leadership, because at the end of the day, their overall seat count is determined by the proportional number and not at all by local numbers, which gives even locally-elected reps a reason to abide by the leadership, on the promise of a preferred list position if the seat should be lost.

As well, it doesn't really cure strategic voting; it merely glosses over its impact at the national level by making the local races not really matter.

So you can see why a lot of NDP partisans, and others disillusioned with traditional party mechanics, really like this type of system. On the surface, it's very appealing to them.

But this is where we need to revisit the assumption that campaign/voting behaviours would look the same. Because they wouldn't. The Liberals and Conservatives have refined campaign engines premised on vote 'efficiency'. The Harper Conservatives were very good at this. Now the Trudeau Liberals are. It's not an accident that their seat counts dramatically outpace their national numbers.

Compare, for instance, York-Weston with Davenport. York-Weston is a Liberal stronghold, whereas Davenport is contested between LPC and NDP. Despite a higher population, York-Weston has a significantly lower voter turnout.

There are two possible explanations for this, both of which are likely true to some extent. One may be that voters behave differently in strongholds. LPC voters in York-Weston are more likely to stay home because they don't need to vote; other voters are more likely to stay home because their votes won't matter. Regardless of the balance, this would be a distortion compared to what PR would look like...though it's difficult to assess impact, because that assumes a level of information about the local race that most voters simply don't have. But the other explanation is clearly present and one-sided: The Liberals focus their ground game on contested ridings. On election day, it's not uncommon to see volunteers from a safe riding 'lending a hand' in a contested riding. Their canvassing and GOTV efforts target marginal voters in ridings they might win or lose. (In some ways, this isn't an ideal mechanic, but it means broader geographical outreach. In order to establish meaningful power, the Conservatives need to expand beyond their rural roots and speak to urban Canadians in some way; conversely, Liberals can't simply focus on their urban centres.)

If you shift to a system like what the LCC recommended - so whether they win a specific seat no longer matters to their overall seat count, but vote percentage does instead - they'll double down on friendlier regions, focusing resources on driving up turnout among voters in higher-concentration Liberal areas.

In other words, this is functionally indistinguishable from the pure PR system I discussed earlier, with parties doubling down on their base, trying to drive up turnout to run up the score locally in the places where they have support.

If you structure the list seats by Province, instead, that results in a different slate of problems.

If you look at the last election numbers...Provincially, some parties got such blowout seat counts for one Province or another that you couldn't make their counts balance proportionally by adding 50% more seats. The CPC would still end up disproportionately represented in Alberta and Saskatchewan; the LPC in Ontario, NS, NL, and PEI. If you're distributing list seats Provincially, PEI only gets two of them, but within PEI there are four national parties with no seats - the CPC with 31.6% of the vote, the NDP with 9.2% of the vote, the Greens with 9.6% of the vote, and the PPC with 3.2% of the vote.

These phenomena also skew the ultimate proportionality, too. The CPC, nationally, would end up with a smaller percentage of seats than their total vote count. The LPC would likely only add something like 16 of the PR seats, if that, but that still leaves them with a higher seat percentage than their vote percentage.

Because of this phenomenon, if we adopted regional lists, the leading parties in at least six Provinces may still end up focusing, regionally, on a vote efficiency calculus, trying to win the FPTP count in as many ridings as possible. {Which may, in fact, be easier to manipulate given that the PR elements in the system will cause people to de-prioritize strategic concerns.) The Liberal campaign in Ontario and the Atlantic Provinces wouldn't change significantly, while their campaign efforts in Montreal, Vancouver, and Prairie cities would.

Constitutional Questions

The constitutional issues are yet another quagmire, and analytically complex because it is effectively a two-part question: To what extent is our electoral structure entrenched in the constitution in the first place; and if reform is required, is the Federal government able to make that reform without Provincial consent?

A transition to IRV/AV is relatively uncontroversial. Most theorists, myself included, agree that changing manner in which we cast and count our votes, to elect one member to represent our district, doesn't engage any constitutional questions. It ultimately doesn't change our representational model in any way, despite the impact it may sometimes have on election results. (Michael Pal, for his part, argues that this requires constitutional reform, but that the reform is within the authority of Parliament - in other words, it doesn't require Provincial consent.)

However, a transition to PR is much more challenging, as it does conflict with both the text and the spirit of the representation structure created by the constitution. In particular, the creation of multi-member constituencies and/or regional/national lists is a significant departure from the basic principle that each district elects one member. Most theorists, myself included, agree that this does require constitutional amendment.

The tougher question is whether or not this is an amendment within the unilateral power of the Federal government, or it requires Provincial consent. The practical reality is that, if it's the latter, such reform is effectively impossible.

Some theorists, like Asher Honickman, Leonid Sirota, and Emmett Macfarlane, argue that s.44 of the Constitution Act, 1982 gives the Federal government the unilateral authority to amend the constitution "in relation to...the House of Commons". Which is true, subject to certain limitations, like the proportion of representation as between different Provinces AND the rule that each Province is entitled to at least as many MPs and Senators.

On the other hand, in other contexts, Leonid Sirota has written of a "consistent pattern of the Supreme Court’s rejection of unilateral constitutional reform".

Others, such as Michael Pal, argue with reference to the Senate Reference that the SCC has rejected unilateralism when it comes to changing the essential character of our Federal democratic institutions, and that this extends to PR. (Macfarlane et al argue that this is distinguishable.)

I tend to come down on the side of Pal here. Saying nothing of how specific judges will resolve the question, it seems to me that different PR-based proposals run into various levels of difficulty, but multi-member constituencies are a pretty fundamental change to the way our Federal government works, and Parliamentarians chosen from lists instead of direct election also seems quite fundamental.

Furthermore, given the fetters on the ability to make changes to the House of Commons, most models would likely create additional problems.

The assignment of seats to different Provinces is a complex mathematical exercise, based on the population of the Provinces, with certain backstops, but for some Provinces, like PEI, the backstop is all. For the most part, Provinces get one seat for every 111k people. PEI, despite having a population of about 150k, gets four, because that's what the constitution says.

So two things are true: The Feds can't unilaterally reduce PEI under four, and the Feds ALSO can't change "the principle of proportional representation of the Provinces in the House of Commons."

Just to get into s.44 - that is, the fight of whether it too fundamentally changes the character of the House - any proposal for change has to stay onside of those.

So...national lists are right out. On that basis alone, additional PR seats, if at all possible, would have to be allocated by Province. But what does that look like for PEI? Are we adding seats on top of their existing minimum of four, despite them not having the population to justify those seats? If, in Ontario, we're adding a new seat for every 220k or so people, but in PEI we're adding a new seat for every 75k people, bringing it beyond its minimum while still leaving it drastically overrepresented by population, doesn't that change the principle of proportional representation?

Conversely, if we add the new PR seats before calculating the minimum, so PEI doesn't get any new seats while everybody else does, doesn't that also change engage constitutionally-protected interests of PEI?

Summary

As I mentioned earlier, as a young undergrad student I would probably have described myself as a PR purist. I never really saw STV as meaningfully accomplishing the goals of PR - just changing what makes a vote efficient, and not removing vote efficiency from the equation.

Now, I altogether question that the goals of PR - aside from eliminating strategic voting - are actually beneficial to the quality of a democracy.

And ultimately, the practical differences between IRV and STV are most significant in how they encourage politicians and parties to deal with non-supporters.

IRV encourages greater accountability and engagement to and with constituents who may support another party, STV does the opposite, encouraging parties to close ranks and focus on their base.

And the STV change to the representational model is pretty disturbing, too. Right now, at least theoretically, a local representative has a mandate to represent everyone in the constituency. I can write to my MP, even though I didn't vote for him, and it would be pretty poor form for him to tell me to go away simply because I'm a non-supporter (i.e. because I'm on record as saying that a rabid trash panda in a blue sweater would get elected in my riding and probably do a better job). Multi-member constituencies tend more to encourage a tribal mentality, where MPs are more likely and quasi-encouraged to provide more support to their own base - which really leaves the (fewer but still existing) 'thrown away votes' disadvantaged in terms of representation.

By contrast, in IRV, a candidate is less likely to tell a non-supporter to go away, and more likely to try to earn a higher preference ranking from them. It's simply a better model for accountability to the constituency.

At the party level, too, the differences are stark: Majority governments aren't totally out of reach in IRV, but they require a party to get a majority of votes (at some preference level) in a majority of ridings, meaning that a party looking to expand its influence must reach out to a wide range voters in a broad range of geographical locales, as opposed to STV where expanding influence will involve either trying to milk more seats out of your stronghold, or else trying to attain threshold support numbers to get individual seats in other regions.

In other words, IRV makes it harder for parties to get away with alienating large blocs of voters; STV makes it easier.

Neither one requires actual majority support to form a majority government. Efficiency remains a phenomenon in both systems, but in STV efficiency means targeting specific thresholds on a riding-by-riding basis, and in IRV it means hitting that 50% threshold most places you target it.

PR (largely including the various hybrid options):

- Institutionalizes the power of regionalist and extremist groups

- Discourages parties from building bridges to demographics of non-supporters

- Strengthens parties and weakens the ties between constituents and their representatives in Parliament

- Is constitutionally dubious

STV:

- Is not proportional.

- Institutionalizes the power of regionalist and extremist groups.

- Would require an extravagantly large Parliament.

- Discourages parties from building bridges to non-supporters

- Is constitutionally dubious

- Preserves the current general structure of our representational system.

- Makes it more difficult for extreme and/or single-issue groups to achieve electoral power.

- Promotes outreach and conciliatory behaviours by parties toward non-supporters.

- Weakens party discipline.

- Is constitutionally straightforward.

Post-script on majoritarian decision-making

The core appeal of STV, to its supporters, seems to simply be the fact that it makes majorities very difficult to obtain. Once a party gets 50% plus 1 of seats, they get 100% of legislative power.

In a majority government, the opposition parties - with their millions of votes - exercise no meaningful weight on policy. In a minority government, the thinking goes, the government must court the other parties to pass their agenda.

Yet, still, they only need 50% plus one.

This is a function of how we make governing decisions generally, that majoritarian decision-making means that for any given controversial decision, the majority gets their way, and the rest get...nothing. Whether that majority is formed from one party, two parties, or more, 100% of the decision-making authority is conferred on the group with 50% plus one votes.

This is the same problem I noted earlier in the Irish context: The Sinn Fein got the most votes, but they're shut out of the governing coalition, whereas the Green Party got 7.1% of the votes, and they effectively have a veto on any legislation. To be clear, I shouldn't be taken here as opposing the Greens or supporting the Sinn Fein; I'm merely pointing out that if your measure of success for an electoral system is allocating effective policy-making power based on the percentage of votes, that type of system simply doesn't fix your concern, but instead replaces one type of distorted power dynamic with another.

Comments

Post a Comment